What makes for a good reading year is still a bit mysterious to me, but I’m learning that part of it is hunger. Sometimes, there’s a subject that captures my heart that sends me in search of answers. Sometimes, it’s the discovery of an author that compels me to read all their works. In this case, hunger came in the form of a project I’m working on that required a bit of research. The bulk of this year was marked by an urgency to plow through as many books as I could, absorb what I needed, so that I could turn around and produce.

So deep was the hunger, so intense was the urgency, I found myself trying to access books for cheap, if not free, by any means necessary. I found free, bought discounted Kindle books, and subscribed to Speechify to have AI read them to me. When I reached a dead end pursuing books through that means, I discovered Perlego, which enabled me to access more academic texts. It just so happened they also had a read-aloud option.

The results speak for themselves. Not just in their quantity (65 compared to last year’s 50) but also in their subject matter. Topically and demographically, it’s arguably the least diverse list I’ve had in a while. That said, it was one heck of a year. There are so many good books I won’t even venture to bullet point my top reads, but what I will say, and what I will give you, is this: over the course of reading, two kinds of books emerged. First were the books that lit a fire in my belly for mission and alternative expressions of the church. The second were the books that made me fall in love with writing and storytelling all over again. So here you go. Not necessarily ranked or intentionally numerical, but some of the standout reads from this past year.

Books that Made Me Fall in Love with the Church

Organic Church — Neil Cole, Houses that Change the World — Wolfgang Simson, Members of One Another — Dennis McCallum, Movements that Changed the World — Steve Addison

When I became a Christian, I came into a certain set of values and a way of being the church that wasn’t common to the bulk of Christian culture at the time. For the longest time, I was afraid to talk about microchurches outside of my ecclesial circle because even though I knew their validity (experientially), I didn’t know how to make a biblical case for it. As time has passed, microchurches are an idea whose time has come. Not only is there a whole conference dedicated to it (next year we’re meeting in Tampa, by the way), but even in church planting conferences like Exponential, microchurches are being heralded as the future of the church. The irony, of course, is that microchurches are actually very old. With that, it can be easy to take a thing for granted. Going back to books like Wolfgang Simson’s Houses that Change the World or Neil Cole’s Organic Church was like rediscovering an ancient text. The fire and conviction they wrote with, partially because they believed in what they were saying, but also because they understood they were writing about something contrary to the prevailing forms of church, made these books more enjoyable. I realized I am attracted to passion, and each of these books came out swinging. These almost feel like required reading for microchurch/network church enthusiasts.

Books that Made Me Fall in Love with Writing

The Anthropocene Reviewed — John Green, The Message — Ta-Nehisi Coates, There’s Always This Year — Haniff Abdurraqib, Bomber Mafia — Malcolm Gladwell

Even though I went to school for creative writing, very rarely do I read anything literary. More often than not, I’m knee-deep in something informative. Truth gets communicated matter-of-factly without much regard for beauty. It’s a transaction between author and reader. Communicating clearly is difficult enough. Communicating beautifully? Well, that’s something else entirely.

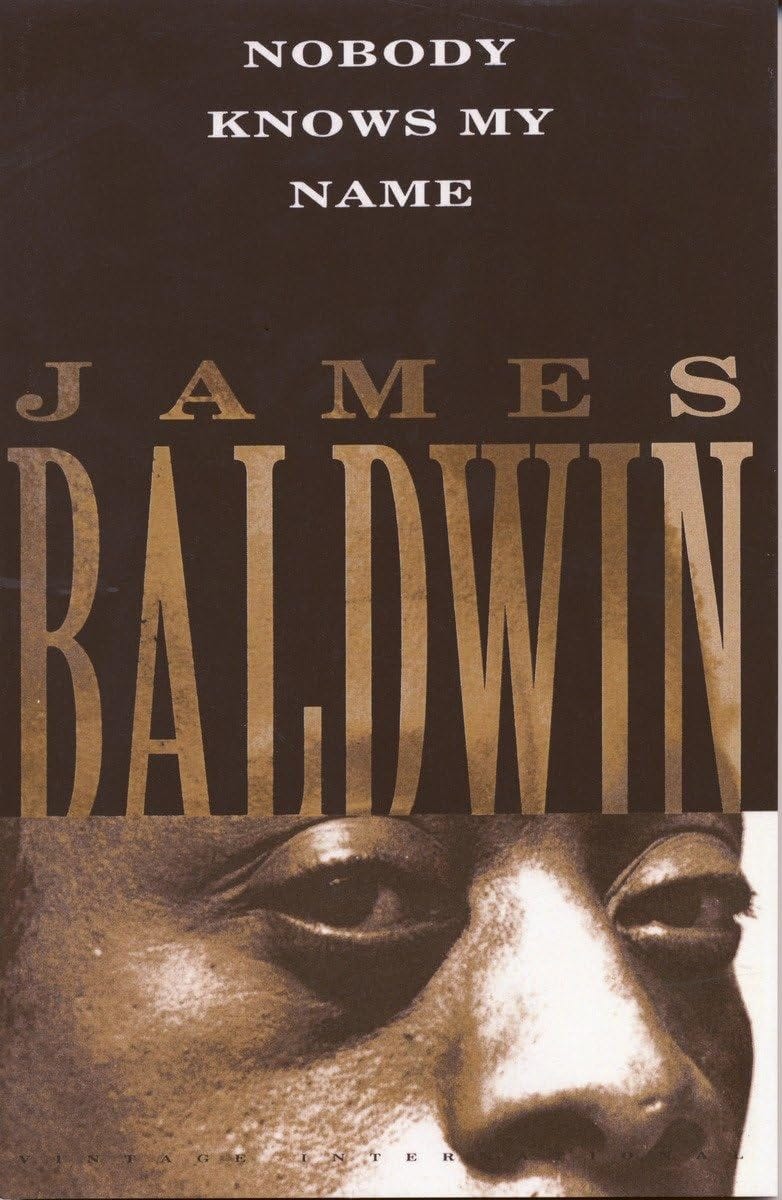

Reading Ta-Nehisi Coates’ The Message reminded me that writing doesn’t have to be transactional. It can be beautiful, engaging, artful. It’s sacred and should be treated as such. Even though Coates is the one who often draws the comparisons to James Baldwin (my favorite nonfiction writer), in my mind Haniff Abdurraqib is the heir apparent. Not because they write the same genre or even about the same subjects, but because Haniff carries both the beauty and the brokenness that Baldwin carried. Coates, perhaps, has the prophetic fire or the incisive eye and language, but he lacks the hope that always tempered and grounded Baldwin and gave him room to be prophetic. It’s only prophetic if there’s also hope attached to it.

What I loved about John Green’s The Anthropocene Reviewed is that through describing and reviewing random objects in the human experience, we don’t just get a sense of those items, we get a sense of him. What makes the book work well is that he is such a genuinely delightful human being, filled with so much compassion and intellect that it’s just fun to listen to him.

These were just good reminders of beauty in an otherwise relatively academic year.

Other Books I just plain enjoyed (because, of course, no list would be complete without some honorable mentions):

The Tipping Point/Revenge of the Tipping Point/Talking to Strangers — Malcolm Gladwell, His Very Best — Jonathan Alter, A Big Gospel in Small Places — Stephen Witmer, The Black Church — Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Belonging and Becoming — Mark and Lisa Scandrette

Seriously, so many other books could have made this list, but I’ll leave it there for now. Here’s to another year of books in the books. I’m excited to see what new discoveries 2026 has for me.

The Full List:

January

1. The Soul of Shame — Curt Thompson*

2. Slow Productivity — Cal Newport*

3. The Fund* — Rob Copeland

4. Blink — Malcolm Gladwell*

5. The Tipping Point — Malcolm Gladwell*

6. High on God* — James K Wellman, Jr., Katie E. Corcoran, Kate J. Stockly.

February

7. Antifragile — Nassim Nicholas Taleb*

8. The Benedictine Tradition — Laura Swan and Phyllis Zagano

9. Chasing Failure* — Ryan Leak

10. The Message — Ta-Nehisi Coates*

11. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass — Frederick Douglass*

12. The Man Who Broke Capitalism* — David Gelles

13. Walt Disney: An American Original — Bob Thomas

14. The Seven Frequencies of Communication — Erwin McManus*

15. Children of Anguish and Anarchy — Tomi Adeyemi*

March

16. Shameless — Nadia Bolz-Weber*

17. Don’t Look Back — Christine Caine*

18. The Azusa Street Mission and Revival — Cecil M. Robeck, Jr.*

19. Organic Church — Neil Cole*

20. God’s Forever Family — Larry Eskridge*

April

21. Church Plantology — Peyton Jones*

22. Talking to Strangers — Malcolm Gladwell*

23. Revenge of the Tipping Point — Malcolm Gladwell*

24. How We Fight for Our Lives — Saeed Jones*

25. The Left Behind — Robert Wuthnow*

26. My Vanishing Country — Bakari Sellers*

27. Big Little Lies — Liane Moriarty*

May

28. There’s Always This Year — Hanif Abdurraqib*

29. His Very Best — Jonathan Alter*

30. Houses that Change the World — Wolfgang Simson*

31. The Gospel of the Kingdom — George Eldon Ladd*

32. Fahrenheit-182 — Mark Hoppus*

June

33. Members of One Another — Dennis McCallum*

34. Subtract — Leidy Klotz*

35. The Anthropocene Reviewed — John Green*

36. Unreasonable Hospitality — Will Guidara*

37. Eight Dates — John Gottman and Julie Schwartz Gottman*

July

38. Organic Discipleship — Dennis McCallum*

39. The Black Church — Henry Louis Gates, Jr. *

40. The Black Church in the African American Experience — C. Eric Lincoln and Lawrence H. Mamiya*

41. Joyful Perseverance — Ajith Fernando*

42. Movements that Change the World — Steve Addison*

August

43. The Bomber Mafia — Malcolm Gladwell*

44. Contagious Disciple Making — David Watson and Paul Watson*

45. T4T — Steve Smith with Ying Kai*

46. Small Town Jesus — Donnie Griggs*

47. A Big Gospel in Small Places — Stephen Witmer*

48. Miracle Work — Jordan Seng*

49. Power Evangelism — John Wimber*

September

50. Evicted — Matthew Desmond*

51. The God Who Makes Himself Known — W. Ross Blackburn*

52. Reset — Chip and Dan Heath*

53. Belonging and Becoming — Mark and Lisa Scandrette*

54. Habits of the Household — Justin Whitmel Earley*

October

55. From Notes to Narrative — Kristen Ghodsee*

56. Teaching to Transgress — bell hooks*

57. Church Turned Inside Out — Linda Bergquist and Allan Karr*

58. Such Great Heights — Chris DeVille*

59. The Presence of the Future — George Eldon Ladd*

November

60. Starfish and the Spider — Ori Brafman and Rod A. Beckstrom*

61. Backpacking with the Saints — Belden C. Lane*

62. Naming the Powers — Walter Wink

December

63. Are You Mad at Me? — Meg Josephson

64. The Power of Positive Thinking — Norman Vincent Peale*

65. Loving to Know — Esther Meek